JACE ROMICK

Jace Romick grew up on a ranch in beautiful Steamboat Springs, Colorado. Jace’s first love, skiing, led to a gratifying career on the US Ski Team, competing in the FIS World Ski Championships and 1984 World Cup downhill events taking him around the. His ranching heritage brought him back to Steamboat Springs and his love of horses drew him into the exhilarating world of rodeo, where he still competes today.

Jace’s extraordinary life experiences continue to influence his powerful photos and creative direction. In addition to creating compelling photographs, Jace also designs and builds custom frames for all his work, using various techniques that he has refined over 30 years of woodworking. By pairing reclaimed wood, distressed metal and hand forged hardware, Jace presents images that are evocative and compelling, offering deep visual appeal.

ROLAND REED

Royal W (Roland) Reed Jr. (1864–1934) was a photographer who documented the ways of eight indigenous American tribes at the turn of the 20th century.

Reed was a noted pictorialist. Influenced by the late 19th century impressionists, Reed’s focus was placed on lighting and focus. Dismayed by the deleterious impact of reservation life on Native Americans, Reed strove to represent his subjects’ lives as they had been in better times.

Reed Immersed himself within the tribes he photographed, overcoming hesitation and often aggression from leaders who opposed his presence. His method was to gain their trust to capture images which were often deeply personal.

Artist's Reception

Friday, August 15

5–8 PM

Thank you for joining us to celebrate with Jace Romick and other appreciators of fine art and history.

Jace

Romick

Click the images below to expand them to full screen.

For more information, pricing and to acquire a new work of art from Old West, New West, please contact a gallery representative at 970-476-9350.

Works are presented with edition number, size and handcrafted frame currently on display at the gallery. Different sizes and framing options are available within limited editions. For further information, please contact a gallery representative.

“RIDING THE STORM OUT”

37×78″ | 2/15

Fine art watercolor print

“COWBOY BAR”

36×36″ | 20/250

Metallic print with acrylic overlay

“WELCOME”

36×36″ | 53/250

Metallic print with acrylic overlay

“RHYTHM”

61×43.5″ | 16/250

Luster print

“PISTOLS”

38.5×54″ | 2/100

Metallic print with acrylic overlay

“MAKE MY DAY”

34×60″ | 68/250

Luster print with Colt-45 bullet mounts

“NAVAJO GIRL”

29.5×39″ | 15/250

Metallic print with acrylic overlay

Custom Frames

Jace Romick believes a frame should be as beautiful as the artwork it secures. To this end, every image he prints hangs in a custom frame, hand-built onsite.

Before opening the gallery, Jace earned a reputation as a fine furniture maker, a self-taught skill he developed over three decades. When the Colorado native opted to concentrate solely on his career as a photographer, he was disenchanted with the finishes applied to much of the Fine Art on the market. Because of this, Jace learned how to hand build frames using traditional methods.

He chooses alder and walnut hard woods, which are cut, distressed, hand rubbed and erected using dovetail miter joints to ensure a handmade look. Each frame is glazed to expose the fine grain in the wood and sealed with a fine lacquer finish. The finished alder frame suggests a refined rustic style, while the walnut offers a more contemporary look or opt for a more streamlined frame with no reveal and your choice of trim.

“NEVER GIVE UP, IT’S THE COWGIRL WAY”

Jace Romick

31×39″ | 3/100

Metallic print with acrylic overlay

“LET YOUR BABIES BE COWGIRLS”

Jace Romick

33.5×47″ | 3/100

Luster print

“ALL IN A DAY’S WORK”

28×59″ | 4/15

Fine art watercolor print

“MOOZ” Triptych

60×27″ each | 34/250

Roland

Reed

Each work by Roland Reed is printed in limited editions on the finest quality metallic paper with a bonded acrylic overlay. This state-of-the-art process ensures a highly detailed image with an incredible depth of value that will last for centuries.

Reed split his collection of indigenous imagery into three categories represented below.

Royal W. (Roland) Reed JR. (1864 – 1934) was a fastidious artist who used photography as his chosen medium to document the ways of eight Indigenous American tribes at the turn of the 20th century. Little is known of this photographer, whose untimely death and lack of resources failed to award him the same recognition as his most notable contemporary, Edward S. Curtis (1868 – 1952).

Curtis created around 40,000 photographs, compared to Reed’s portfolio of several hundred images. However, Reed was self-funded, self-directed, and adverse to commercialism. He was driven by a deep appreciation for the indigenous population and his own necessity to document their historic practices for future generations.

Reed was born in Omro in the Fox River Valley, Wisconsin in 1868, four years earlier and 100 miles away from Curtis. He was the fourth of six children, only he and his sister Mabel made it to adulthood. The family’s log cabin sat along a popular trail frequented by a band of the Menominee tribe. At age seven his fascination for “Indians” arose after two fellow pupils were saved from a near drowning incident by three Menominee, one of whom was a chief named Thundercloud. Reed declared him, his childhood hero.

-

When Reed turned 18, he apprenticed as a carpenter before setting off to work in a sawmill in West St. Paul. It turned out he wasn’t keen to stay in one place and landed a job with the Canadian Pacific Railroad. His travels with the railroad lasted many years and exposed him to various tribes who continued to capture his interest. An accident at work in Winnipeg forced him to spend time recuperating and led to a short-lived return to Minnesota.

In his journal he said “The Indian was upper most in my mind, don’t know why, but no trip I could plan satisfied me unless it led into Indian country, so I began to plan a trip down the Mississippi River. This plan matured when I had a chance to be shipped to below Memphis, Tenn. to work on the levy.”

Reed made his way south to explore Arkansas, Texas, New Mexico, and the lands of the Apache. He saw first-hand the impact of reservation life and his motivation to tell the story of native ways as they were, was ignited.

He secured another job with the railroads, this time with the Great Northern Railway. He made his living through sketching and portraiture, portraying the life and ways of the indigenous people of the Plains.

A chance meeting in 1893 with Daniel Dutro, a professional portrait photographer with a studio in Havre, Montana would alter the trajectory of Reed’s career. When he saw how quickly he could work with the aid of a camera, he entered an apprenticeship with Dutro and earned his living taking pictures. In 1897 Reed was hired by the Associated Press in Seattle to photograph the Klondike gold rush in Alaska, and he was back on the road.

In his own journal he recalled the experience “I found no gold but spent most of what money I had in supplies to carry me through winter. I found several villages of Indians along the coast in the vicinity of the mouth of Diea Creek. They were an honest hospitable and kindly people, but a very poor representative of the North American Indian. They made such a poor impression on me that I left for the states on the first ship south in the spring without making any pictures worthwhile.”

Within a year he returned home and decided to open his own photography business the Reed Studio in Ortonville, Minnesota. His reputation as a portrait photographer soon preceded him and he opened a second studio in Bemidji, Minnesota, very close to land occupied by the Ojibwe. Once again, Reed found himself in the right place and the right time, and in 1907 he handed over his studio, packed his bags and set off on his mission to “start on my long-deferred campaign in portraying the North American Indian.”

By the turn of the 20th Century, it was widely believed Native Americans were a ‘vanishing race.’ The United States government had already forced tribes off their lands and strived to strip them of their customs and traditional ways of life.

The indigenous people were not wiped out as was thought would happen, but many of their traditions were irrevocably lost. It is to this end, Reed’s work, like that of his contemporaries did in fact prove to be a valuable record.

Reed was a pictorialist, a term derived from an artistic movement introduced in the 1860s in Europe. Pictorialism inspired self-expression in imagery through tonality and composition, rather than the traditional scientific approach to photography of the era.

Like Curtis, Reed wanted to represent the Native Americans in their glory. The U.S. government decimated much of their cultural norms by forcing indigenous children into boarding schools, cutting their hair, and banning the use of native languages. Reed went to great lengths to capture scenes, to portray the old way of life in all its tradition and majesty. His work emanates cultural pride and the unmistakable bond shared by a people and their land.

Reed immersed himself within the tribes he photographed, overcoming hesitation and often aggression from leaders who opposed his presence. His method was always to gain their trust and garner permission to capture images which on some accounts were deeply personal.

In a letter to an editor of the Minneapolis Journal dated April 2, 1923, Reed described his ability to achieve his portfolio of imagery. “In approaching the Indian for the purpose of taking his picture, it is necessary to respect his stoicism and reticence which have so often been the despair of the amateur photographer. A friend once characterized my method of attack as indicative of Chinese patience, book-agent persistence, and Arab subtlety. In going into a new tribe with photographic paraphernalia, although I hire ponies, wagons, guides etc., I never once suggest the object of my visit. When the Indians, out of curiosity at last, inquire about my work, I reply casually, “Oh, when I’m home, I’m a picture taking man.” Perhaps within a few days an Indian will ask, “You say you are a picture-taking man; could you make our pictures?” My reply is non-committal, “I don’t know – perhaps.” “Would you try?” “Sometime, when I feel like making pictures.” Further time elapses: apparently the picture taking man has forgotten about making pictures until an Indian friend reminds him of his promise – and then the time for picture-making has arrived. They are imbued with the subject I am trying to depict and the pose in all earnestness.”

Reed’s images were limited to eight tribes – the Ojibwe in Minnesota, the Blackfeet, Piegan, Flathead, Cheyenne and Blood in northern Montana and southern Canada, and the Navajo and Hopi in Arizona.

He was meticulous in the detail for each image, using only authentic artifacts, often moving props from tribe to another. Towards the end of his career, he said it would no longer be possible to achieve what he had done for so many of the artifacts had been sold to tourists. Like Curtis, he chose to share a narrative perspective of the scenes he captured. Subjects were staged and evidence of modern intervention was removed or hidden from view. He wanted to share a story of the past, which was welcomed by his subjects.

In a personal description of image “Tribute to the Dead” circa 1912 Reed said “You may imagine the difficulty I experienced in finding a family ready to have a funeral and in making them revert to this old, abandoned custom. Then, when I secured their consent, I was told by an old Indian that I couldn’t get it as it really used to be, because there were no more complete Buffalo hides with head and tail left on, such as they used to wrap the bodies in. I knew a woman in Kalispell who had an old head and tail hide and we postponed the funeral until I could go to Kalispell and induce her to lend it to me. Everything you see in that picture is correct; it might have been taken 100 years ago.”

Reed’s time in Kalispell amounted to some of his most prolific work. He formed part of an artistic community and close friends included painters Charles M. Russell, Johannes Anderson, and Julius Seyler. Each one had an affiliation to what became Glacier National Park in 1910. Reed’s portrait of Russell taken in 1921 is one of his most famous images today. During Reed’s time in Montana, he was welcomed by the Blackfeet and given the Indigenous name, Big Plume.

In 1914, Reed made San Diego, California his base with a new studio. His work captured the attention of the executives of the Southwest Society, the western branch of the Archaeological Institute of America. He was selected to be part of the 1915 Panama-California Exposition with an exhibit in the Southwest Museum, now part of the Autry National Center. It marked a high point in his career.

In an article published by the Kalispell Bee on January 10, 1913, it read “Roland Reed is perhaps the peer of any artist in the world in his own line. For years he has made a study of the ways of the North American Indian, has lived and worked among many of them and in his time secured some of the most wonderful pictures ever taken of them. His collection will someday be the most valuable of its kind in the world and will net Mr. Reed a fortune.

That fortune never materialized. Although he sold a limited number of photographic rights to National Geographic Magazine and the Great Northern Railway, he shunned any commercialism of his indigenous photography collection. He turned down an offer of $15,000 for approximately 200 negatives, which would have been much of his work. Instead, he relied on his portrait photography to afford a humble living.

From 1920 to 1927, Reed opened two more studios, one in Red Wing, Minnesota and another in Denver, Colorado. Later in life, he intended to publish a book titled “Photographic Art Studies of the North American Indian,” not for commercial gain, but as a method of educating future generations. He was working on it with his cousin Roy Williams when he passed away suddenly.

On November 10, 1934, while visiting friends Reed slipped on a banana peel and suffered a fracture of the thoracic vertebra. He developed inflammation of the spinal cord and died on December 10 at St. Francis Hospital in Colorado Springs. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Evergreen, Colorado. His life’s works became the property of Roy Williams.

In 2012 Ernest R. Lawrence published a book, Alone with the Past, The Life and Photographic Art of Roland W. Reed, which was declared “as close to a catalogue raisonné as will be for Roland Reed,” by Sandra Starr, a senior researcher for the department of history and culture at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. The same year, Lawrence and a small group of supporters donated a headstone to commemorate an artist who earned his place in history.

The People of the Plains

“The Native Americans of the Great Plains, designated as the Buffalo or Pony natives roamed the far-flung prairie country between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. He is shown in the photographs as the Piegans or Blackfeet and the Cheyenne.

I have been accepted as a member of the secret fraternal order of the Blackfeet called Big Medicine Lodge. Upon my initiation in this lodge, I was given the name meaning Big Plume by which I am known among my Native American friends.”

“THE EAGLE” c. 1912

50×40″ | 4/75

“CHIEF, FULL HEADDRESS PROFILE” c. 1912

20×16″ | 2/75

“PROUD HERITAGE” c. 1912

20×16″ | 2/75

“LAZY BOY” c. 1912

58×38.5″ | 6/50

Indians such as Lazy Boy fought the white man for over one hundred years. They were trying to keep their hunting grounds from being broken up and ruined for the Indian mode of living.The eagle-feathered war bonnet was developed and first used only by the Indians on the Great Plains of the West. Not until Eastern Indians had been forced back by the whites and had come in contact with the Plains, or Pony, Indians, did they see an eagle-feathered war bonnet. Now all Indians wear them, and they have lost the meaning that they once had. Each courageous or worthy deed that an Indian accomplished entitled him to wear an eagle feather in his hair. (Women did not wear feathers in their hair.) When an Indian man had earned five eagle feathers, or had become known as a “five-feather” Indian, his fellow braves could vote him the right to wear a war bonnet. The war bonnet of the Plains Indian was a symbol of achievement.

The Boy Scouts have taken their idea for merit badges from that tribe. It was quite a task to kill an eagle with a bow and arrow, and each golden, or war-eagle killed supplied only from six to eight feathers suitable for use in a war bonnet. A single feather might be worth as much as two ponies, so it is readily seen that a headdress of thirty or more feathers represented considerable wealth to the wearer.

The bonnet seen here shows the eagle feathers. Hair from the tail of a white horse has been glued to their tips and is hanging down the warrior's back. The fluff across the base of the eagle feathers is eagle down. The white strips hanging in front of the warrior's ears are made from white winter-killed weasel or ermine fur. Across the forehead is a beaded band, and other beads further decorate it.

“HUNTING GROUNDS” c. 1912

28×59″ | 1/75

The People of the Woodlands

“The Woods or Canoe Native Americans, many of whose ancestors at one time inhabited the Atlantic and who later lived in the vast forest south of the Great Lakes is represented by the pictures of the Ojibway.

During 1907 and 1908 I made several trips to Red Lake, with the valuable help of John G. Morrison, Indian Trader, and founder of the Cross Lake Indian School at Ponema. He was my interpreter when I made the Moose Call, the Hunters, Ringing Bells, Reflections, At the Spring and others. He showed me where mistakes could be made in assembling apparel and accoutrements pertaining to each activity. It was through his advice and knowledge of the Ojibway that I was able to secure a set of negatives of such historical value.”

“THE FISHERMAN, OJIBWE” c. 1908

40×32″ | 4/75

Lantern Slide No. 32

The Fisherman

The following description is from Roland Reed’s handwritten notes.

The Indian of long ago could go into the woods and, with only a sharp piece of stone as a tool, make a serviceable fishing outfit. A small tree, preferably an ironwood, was cut down and peeled. Then the flint knife was used to shape prongs on the butt end of the pole. The prongs were scraped as smooth as possible, then hardened by being held over the fire. A splinter of bone might be counter-sunk in the inside of the prongs to prevent the fish from slipping off when speared. Bark stripped from a moosewood bush was woven into a rope for the spear. The Indian boys and girls gathered spruce and tamarack gum, and pitch from pine trees. This, when boiled with a little venison tallow, made fine pitch for rendering their canoes water tight. The bark from the roots of trees, preferably the red cedar, was used to sew the birch bark together and to fasten it to the braces of the canoe.

“MOOSE CALL, OJIBWE” c. 1908

30×24″ | 1/75

Lantern Slide No. 4

The Moose Call

The following description is from Roland Reed’s handwritten notes.

The Indians of long ago could imitate the call or cry of any animal or bird. This Indian has a roll of birch bark and is “calling the moose.” A moose may be feeding back in the woods, and, hearing what seems to be the call of his mate, may answer. Then he will start for the lake from where he thinks the call came, and where he thinks his mate will be drinking, or feeding on lily pads. The Indian hunters will be hiding in the brush on the lake shore, and, when the moose appears, they will try to get in a telling shot with their stone-tipped arrows. If they are successful, the camp will have a “moose-meat feed.” This Indian's name was Ke-ne-we-gwon-ay-aush, or Eagle-Feather-Wind.

“As I watched them file along the forest trail, I longed to join them, and as I grew into manhood and left my native state, the call of those old friends of the forest and lakes never left me. I could ask for no greater honor at this late date to meet and shake the hands of those fine Indian boys who passed my forest home so many years ago.”

“EVERYWIND, OJIBWE” c. 1908

40×32″ | 1/75

Lantern Slide No. 27

Everywind

The following description is from Roland Reed’s handwritten notes.

This is a fine profile picture of an Indian girl. Its simplicity is especially appealing. Everywind, who, in the Indian language, was called Ain-dus-o-oon-ding, was about eighteen years old when this picture was taken. She, undoubtedly, was very proud of her beautiful Hudson Bay blanket, which she perhaps secured in exchange for buckskin moccasins beautifully decorated with her beadwork.

“PAPOOSE, OJIBWE” c. 1908

20×16″ | 2/75

Lantern Slide No. 5

Little Papoose Pack-a-Back

The following description is from Roland Reed’s handwritten notes.

This little fellow is not missing anything. His bright eyes see every squirrel, chipmunk, and other moving object about him. His mother is carrying him in the Indian baby carrier (called "tickanogan" by some tribes). There were many types of baby carriers, of which this is one. The back of it is probably a board, hewn out of basswood. To this is fastened a pocket, or pouch, made of deerskin, in which the baby is snugly laced. The mother has tucked moss or fluffed cat-tail around the child to keep it comfortable. While working in the garden or picking berries, she may hang the carrier on a low limb of a tree or lean it against a tree. There is slight danger of the little fellow's getting hurt, for the framework above his head acts as a bumper --it would strike the ground first. If it should rain, the mother will draw the shawl over the frame above, and the papoose will be inside, “as snug as a bug in a rug.”

The People of the Southwest

“The Southwestern nomadic Native Americans are portrayed in the pictures of the Navajos who occupied the great plateaus covering parts of Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, and Colorado. They are nationally famous as rug weavers and silversmiths and are often called the Shepherd of the Hills.

The large Pueblo group who inhabits the high plateaus of the Southwest, the only non-nomadic native tribe, live in permanent communal centers. These Native Americans are more agricultural, but they are especially recognized for their beautiful pottery and other works of art. The pictures of the Hopi illustrate this group.”

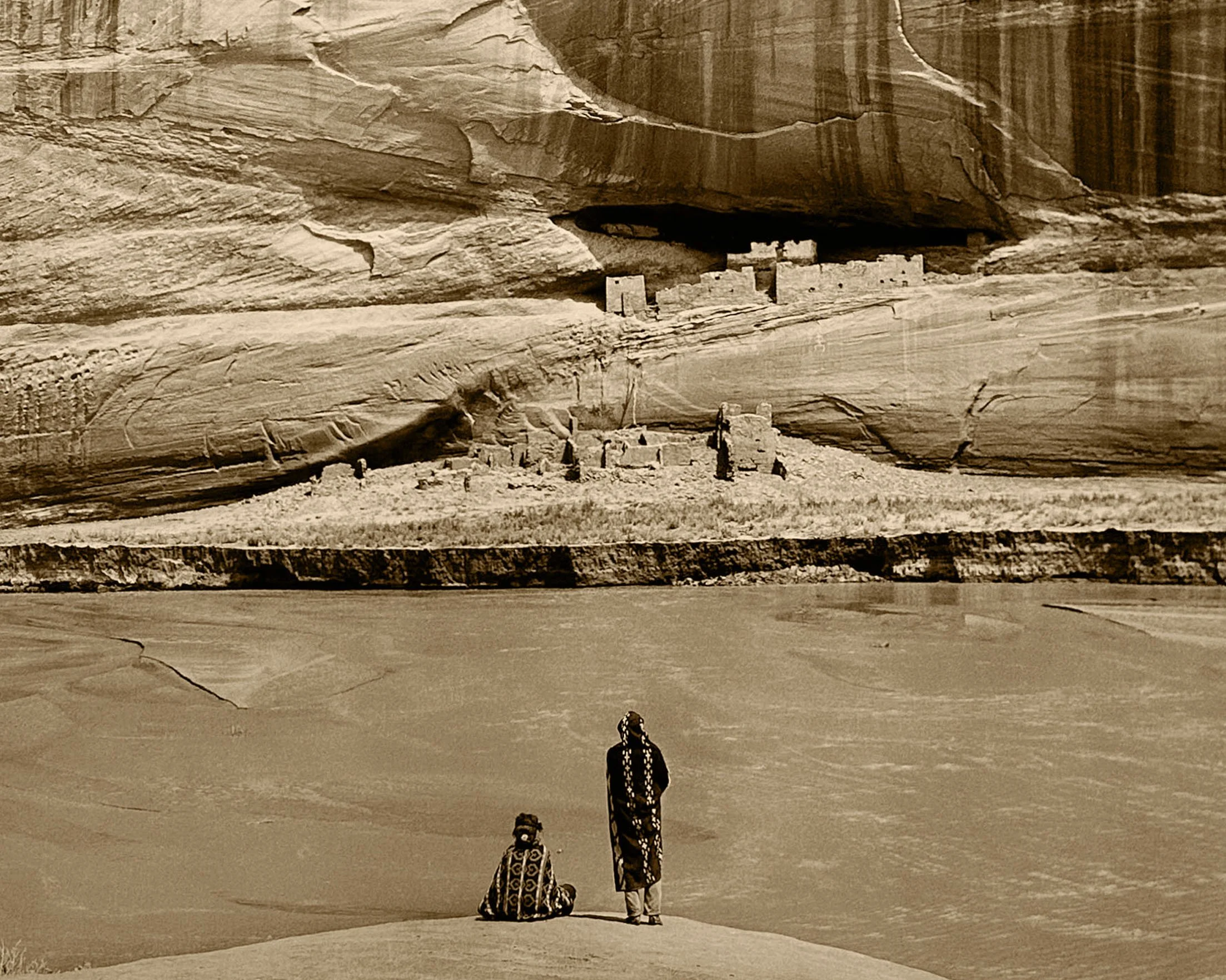

“ALONE WITH THE PAST” c. 1913

40×32″ | 3/75

Lantern Slide No. 49

Alone with the Past

The following description is from Roland Reed’s handwritten notes.

In the foreground we see two Indians looking cross the River of Time at what may be the ruins of their ancestors' home. Little is known about the Cliff dwellers; from where they came or where they went, we can only guess. They must have had consider-able ability as engineers and builders to be able to construct these stone buildings. It is seventy feet from the lower buildings to the shelf in the canyon wall on which the upper ruins rest. We know that this ancient people whitewashed the walls of the rooms, because the whitewash is almost as fresh today as when it was put on--a thousand years ago. We know, too, that they raised corn, beans, and squashes, because the seeds have been found in the ruins. Note how water, through the ages, has colored the canyon walls.

“SUN CHASER” c. 1913

30×24″ | 3/75

“THE WEAVER” c. 1913

16×20″ | 1/75

“SHEPHERD OF THE HILLS” c. 1913

30×24″ | 3/75

Lantern Slide No. 22

The following description is from Roland Reed’s handwritten notes.

For many decades the desert winds flew across the face of this old Navaho Indian. His hair was silvery white, but his hearing and eyesight were still keen. "Many Goats" was his real name, and he was well off, owning large flocks of both sheep and goats.

He was a silversmith. The coins that hung down his back and up under his arm were his stock of silver. The most recent coin was minted in 1897. If anyone wanted a buckle or bracelet, Many Goats would take off enough coins to get the necessary silver. The Navahos constitute the largest Indian tribe. They are a thrifty, an industrious, and a proud people. If they had good land, they would rate with any farming group in America.

Images and information courtesy of Jace Romick Gallery & Roland Reed Gallery.